Case Study as part of a Web-based

Technical and Regulatory Guidance

Iron Mountain Mine

Shasta County, California

1. Site Information

1.1 Contacts

Rick

Sugarek

EPA Site Manager, US EPA Region 9

75 Hawthorne Street

San Francisco, CA 94015

Telephone: 415-947-3256

http://yosemite.epa.gov/R9/SFUND/R9SFDOCW.NSF/VIEWBYEPAID/CAD980498612?OPENDOCUMENT#descr

State Water Resource Control Board: www.swrcb.ca.gov

1.2

Name, Location, and Description

Site Name: Iron Mountain Mine

Location: Nine miles northwest of the City of Redding in Shasta County, California.

Longitude 122.50149, latitude 40.67868.

Figure 1-1. General site location maps.

From the 1860s through 1963, the 4,400-acre Iron Mountain Mine (IMM) site was periodically mined for iron, silver, gold, copper, zinc, and pyrite. Though mining operations were discontinued in 1963, underground mine workings, waste rock dumps, piles of mine tailings, and an open mine pit still remain at the site. Historic mining activity at IMM has fractured the mountain, exposing minerals in the mountain to surface water, rain water, and oxygen. Sulfuric acid forms when pyrite is exposed to moisture and oxygen.

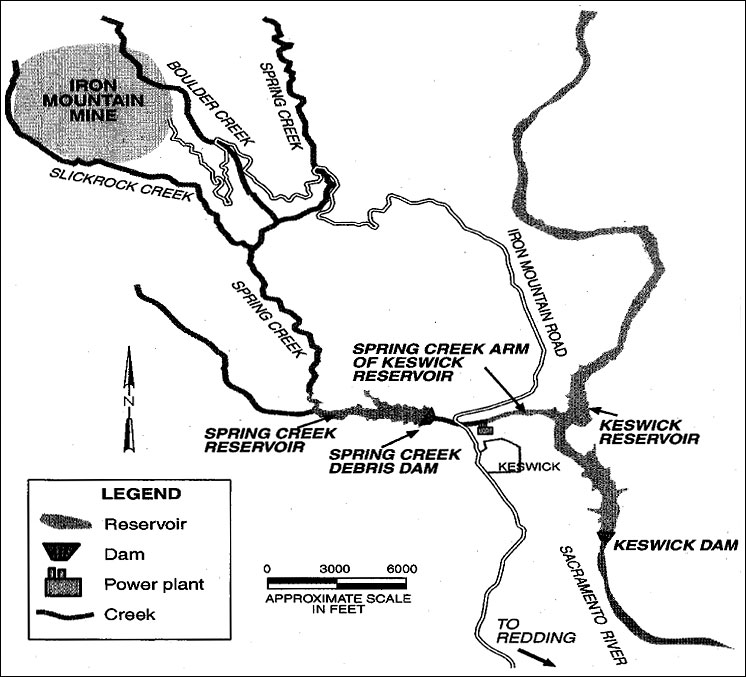

The site comprises 4,400 acres. The Richmond Mine of the Iron Mountain copper deposit contains some of the most acid mine waters ever reported. Values of pH have been measured as low as −3.6, combined metal concentrations as high as 200 g/L, and sulfate concentrations as high as 760 g/L. This sulfuric acid runs through the mountain and leaches out copper, cadmium, zinc, and other heavy metals. This acid flows out of the seeps and portals of the mine. Much of the acidic mine drainage is ultimately channeled into the Spring Creek Reservoir by creeks surrounding IMM (Figure 1-2). The Bureau of Reclamation periodically releases the stored acid mine drainage into Keswick Reservoir. Planned releases are timed to coincide with the presence of diluting releases of water from Shasta Dam.

Figure 1-2. Detailed site area map.

2. Remedial Action and Technologies

Surface water has been contaminated by the release of sulfuric acid, copper,

zinc, and cadmium from the mine. People face a health risk if they accidentally

ingest or come into direct contact with mine drainage. There is a potential

for accumulation of contaminants in fish. The unplanned release of contaminants

acutely toxic to aquatic life has contributed to the steady decline in fish

populations and has contributed to the listing of the Winter Run Chinook Salmon

as an endangered species.

This site is being addressed in six stages: emergency actions and five long-term remedial phases focusing on water management and cleanup of major sources in Boulder Creek, the Old Mine/ No. 8 Mine, area source acid mine discharge (AMD) discharges and sediments.

Emergency Actions: A lime neutralization process was installed at the site to treat acid mine discharge from the Richmond Portal prior to discharge to the reservoir. This system was operated by the EPA during the winter rainy season of 1988 until 1989. Rhone-Poulenc, Inc., a potentially responsible party, operated a similar system during the 1989–1990, 1990–1991, 1991–1992, 1992–1993, and 1993–1994 rainy seasons.

Water Management: In late 1986, the EPA selected cleanup remedies addressing several parts of the water management area. Cleanup activities include capping selected cracked and caved ground areas, diverting clean Upper Slickrock Creek water around waste rock and mine tailing piles, diverting Upper Spring Creek, diverting clean surface water in South Fork Spring Creek to Rock Creek, enlarging the Spring Creek debris dam, and performing hydrogeologic studies and field-scale pilot demonstrations to better define the feasibility of controlling AMD formation. The studies and pilot demonstrations were completed. In 1989, the EPA completed capping cracked and caved ground areas and the open pit mine on Iron Mountain. The EPA completed the diversion of Slick Rock Creek in early 1990. Rhone-Poulenc completed construction of the Upper Spring Creek diversion in early 1991. EPA has not constructed two of the actions, the South Fork Spring Creek Diversion and the enlargement of the Spring Creek Debris Dam. EPA has proposed an alternate treatment approach that eliminated the need for these water management actions.

Richmond Mine and Lawson Tunnel AMD Discharges: The EPA completed its study of the nature and extent of major point source contaminant sources in the Boulder Creek Watershed. In late 1992, the EPA selected an interim remedy to treat the AMD discharges from the Richmond Mine and Lawson Tunnel by constructing collection and conveyance systems and a lime neutralization treatment plant. The treatment plant has been built and has been operating since 1994. Treatment will continue until an alternate remedy can be developed to recover metals or control the discharges to ensure meeting all cleanup goals.

Old Mine/No. 8 Mine AMD Discharges: The EPA has studied the nature and extent of contamination that discharges from the mine seep that originates from the Old Mine and No. 8 Mine. In the fall of 1993, the EPA selected an interim cleanup remedy, which included collecting and treating the AMD discharges from these sources. A collection and conveyance system and a treatment system have been built and have been in operation to treat these AMD discharges since 1994.

Slickrock Creek Area Source AMD Discharges: The EPA completed its study of the nature and extent of the area source AMD discharges from the Slickrock Creek drainage at IMM. In September 1997, EPA selected a remedy that relies on the collection and treatment of the contaminated Slickrock Creek flows to establish significant additional control of the IMM AMD discharges. In September 2000 EPA completed the construction of a clean water diversion system, a 5-acre sedimentation basin, surface water controls, a small earthfill embankment dam, and a conveyance pipeline to ensure the collection and treatment of the contaminated discharges at the existing treatment plant. Only minor modifications to the IMM treatment plant were required to implement this additional treatment effort.

Spring Creek Arm of Keswick Reservoir Sediments: The EPA completed its study of the nature and extent of contamination associated with sediments downgradient of IMM that are located in the Spring Creek Arm of Keswick Reservoir. In September 2000 EPA selected a remedy that provides for dredging approximately 200,000 cubic yards of copper and zinc contaminated sediments from the Spring Creek Arm of Keswick Reservoir.

In August 2008 the EPA initiated construction of the first phase of this cleanup action by constructing access roadways and clearing the disposal cell area. EPA expects to complete the construction of the project infrastructure and perform the contaminated sediment dredging operations over the next three to four years.

Boulder Creek Area Source AMD Discharges: The EPA continues to collect data to characterize the nature and extent of Boulder Creek area source AMD discharges. The EPA is continuing to study potential remedial approaches for the area source AMD discharges from the Boulder Creek drainage.

3. Performance

The installation and operation of the full-scale neutralization system,

the capping of areas of the mine, and the construction and operation of the

Slickrock Creek Retention Reservoir to collect contaminated runoff for treatment

have significantly reduced the acid and metal contamination in surface water

at the Iron Mountain Mine site. Cleanup activities are continuing, and additional

studies are taking place. The diversion of Upper Spring Creek has greatly

increased the ability of the EPA and the Bureau of Reclamation to manage

the continuing release of contaminants from the site to minimize harm to

the Sacramento River ecosystem until a final remedy can be selected and implemented.

IMM was placed on the list of the nation’s most hazardous waste sites, known as the Superfund National Priorities List, in September 1983. Since that time EPA has studied the sources of the AMD and has carried out several emergency response and long-term cleanup actions to reduce the AMD entering the Sacramento River ecosystem. EPA collects AMD from all of the underground mines and the area wide sources in Slickrock Creek and treats the AMD in a lime neutralization treatment plant. After completing the Slickrock Creek Retention Reservoir in 2004 to collect AMD discharges from the Slickrock Creek watershed for treatment, EPA now prevents 98% of metals from the entire mine property from entering the Sacramento River.

4. Costs

Cost of activities at these site are reported as a total:

- Capital: $200 million (estimated)

- Operation and maintenance: $5–6 million per year (estimated)

5.

Regulatory Challenges

In 1989, the EPA ordered the potentially responsible parties to implement

emergency response corrective measures to remove the metal contamination.

In 1990, the EPA, under an Administrative Order, required the parties to

implement the Upper Spring Creek diversion cleanup action. In 1991, the EPA

ordered the potentially responsible parties to assume responsibility for

operation and maintenance of the completed cleanup actions. In 1992, the

EPA ordered the potentially responsible parties to construct the treatment

system for the Boulder Creek Watershed. In 1993, the EPA ordered potentially

responsible parties to implement the collection and treatment system for

the acid mine drainage discharges at the Old Mine/No. 8 Mine.

6. Stakeholder

Challenges

No information available.

7. Other Challenges and Lessons

Learned

Long-term treatment is not the final answer. The system is very expensive

($5–7 million/year) to operate. Further, the disposal area for the sludge

will reach capacity in the year 2030. Some “new and improved” remedial system

is necessary. Research is needed to develop new technologies.

8. References

Nordstrom, D. K., and C. N. Alpers. 1999. “Negative pH, Efflorescent

Mineralogy, and Consequences for Environmental Restoration at the Iron Mountain

Superfund Site, California,”pp. 3455–62 in Proceedings, Geology,

Mineralogy, and Human Welfare, Irvine, Calif., Nov. 8–9, 1998. National

Academy of Sciences, vol. 96.

USEPA Iron Mountain Mine Superfund Site. 2009. “EPA Accelerating Cleanup Efforts at Iron Mountain Mine Site Supporting Local Economy with Recovery Act Funds.” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 9, San Francisco.